SHARE

Thoughts

It is interesting reading the comments [1] to the proposed ruling by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors [2]. Points raised are diverse, but broadly fall within one of two camps; those vehemently opposed to the ruling, and those in support (often calling for more ambitious requirements over and above the proposal from the SEC). This binary grouping is neither surprising nor unexpected for the SEC, given the organization’s four-decade history of contests concerning environmental proposals. [3]

And now in 2022, the SEC is proposing extensive new disclosure requirements for publicly listed firms starting in the fiscal year 2023 (for filing in 2024) for the largest filers – those with a public float greater than $700m – with phased introduction for firms with smaller public floats. The first compliance date will impact around 2,000 businesses and eventually impact approximately 7,000 in total. The requirements require registrants to include certain climate-related information in registration statements and periodic reports, such as on Form 10-K, including:

- Climate-related risks and their actual or likely material impacts on the registrant’s business, strategy, and outlook

- Climate-related risks and relevant risk management processes

- Greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions

- Climate-related financial statement metrics

- Climate-related targets and goals, and transition plan, if any.

The disclosure requirements are centered around the recommendations from the Taskforce on Climate Related Disclosures (TCFD). The SEC joins eight jurisdictions that have TCFD-aligned official reporting requirements, (Brazil, European Union, Hong Kong, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom). Additionally, the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation announced a new International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) to develop a comprehensive global baseline of high-quality sustainability disclosure standards to meet investors’ information needs.

What is TCFD?

As a high-level summary, the TCFD recommendations provide a framework for businesses to identify, evaluate, manage and monitor climate related risks and opportunities. They are centered around four themes, with a total of 11 recommended disclosures.

- Governance – what role do people play in managing and overseeing climate related issues?

- Strategy – how will organizations change to manage future climate-risk?

- Risk Management – what processes are in place to identify, manage and assess risk?

- Metrics and Targets – how do you measure progress against climate-related goals?

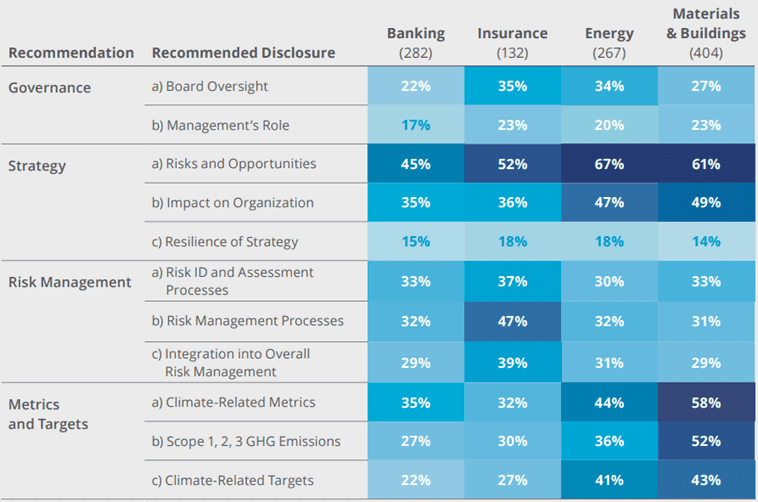

Globally, there are over 3,400 TCFD supporters, although not all of these have disclosed in full yet. The TCFD 2021 Status Report [4] provides a breakdown of public reporting against each of the recommended disclosures; the Materials and Buildings sector captures commercial real estate, although the 404 firms reporting will not be exclusive to the buildings sector.

The results suggest that:

- Most firms are disclosing qualitative risks and opportunities – per Recommendation: Strategy a)

- Materials and Buildings have highest level of Metrics and Targets disclosure

- Scenario analysis is disclosed by only a small percentage of firms – per Recommendation Strategy c)

- Governance, including Board and Management oversight of climate risks and opportunities, is the next least well disclosed theme after scenario analysis – per Recommendation: Governance a) and b)

On the latter point, gaining Board buy-in and a commitment to climate-related topics is essential for strategies and risk management processes to be truly integrated. Without this, firms will be disclosing under the TCFD framework for compliance reasons only – a missed opportunity.

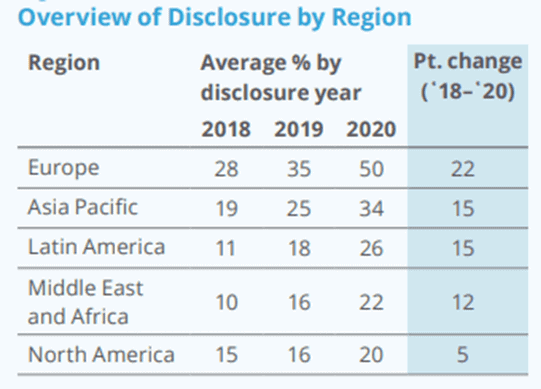

Disclosure rates against the 11 recommendations differ by region, with Europe leading over the period from 2018 to 2020. Double digit increases over two years were seen across all regions, with the exception of North America, which also has the fewest percentage of firms disclosing against the 11 recommendations. The takeaway from these numbers is that the SEC is leap-frogging the comfort zone for many North American firms.

GHG data and data quality

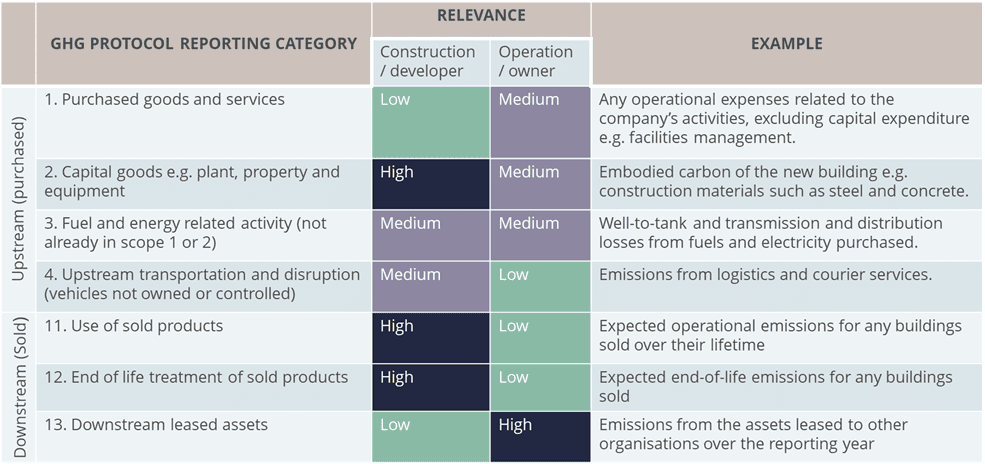

The proposed SEC ruling requires registrant’s direct GHG emissions (Scope 1) and indirect GHG emissions from purchased electricity and other forms of energy (Scope 2) to be disclosed in absolute terms (by Scope) and as an intensity metric. Scope 3 emissions – of which there are 15 categories covering indirect upstream (i.e. related to goods or serviced purchased) and downstream (i.e. related to goods or service sold) – are, receiving a lot of attention due to the fact that Scope 3 emissions are out of direct control of landlords and data quality and coverage is often poor. Aside from small reporting companies, Scope 3 needs to be reported from FY 2024 (filing in 2025), if material.

Defining materiality is not an exact science and the lack of guidance from the SEC may result in reporting opt-outs where Boards deem the organization’s emissions to be immaterial to investor decision making. However, the quantity of emissions (tons CO2) is one method of determining materiality; the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) sets a threshold for materiality as 40% of Scope 3 in relation to Scopes 1 and 2. Other factors influencing materiality need to be considered, such as:

- Risk – considering relevant climate-related legislative and reputational risks

- Influence – the registrant’s influence over emissions generation and reductions e.g. percentage ownership and / or a board representation within investee companies

- Financial – emissions associated with a high level of spend or those generating a high level of revenue.

Many of these factors will need to be considered on a case by case basis, particularly legislative risks, which will need to be considered country by country and at the city level in many instances. For large-accelerated and accelerated registrants there are additional requirements, which will have ramifications for the entire real estate industry, for limited assurance (phased introduction from 2024 for filings in 2025) and the more stringent reasonable assurance (phased introduction from 2026 for filings in 2027). While public REITs [5] are clearly in the SEC’s crosshairs, so too are others in the real estate value chain. For example, lenders (of both debt and equity investments) will need to report their share of Scope 3 financed emissions – most likely following PCAF [6] guidance. Similarly, corporate tenants will want to understand their upstream GHG impacts where energy is provided as part of a service e.g. where a landlord procures energy in a building and recharges costs to tenants. The proposed rules will surely impact both contractual lending and leasing agreements on data provision and, importantly, the underlying quality of that data.

Transition plans

Scope 3 emissions also need to be disclosed in a filing if a registrant has made a transition plan (decarbonization target) public that includes Scope 3. For real estate, it is common to see leaders in ESG set net zero carbon targets that include Scope 3, but this is often ringfenced as tenant energy use. As the table below indicates, there are other Scope 3 emissions that may be materially relevant beyond tenant energy use, including embodied carbon of new construction and refurbishments. How the industry responds to this requirement will be interesting to watch. REITs that understand their full Scope 3 position will be able to retain existing climate goals. Those who do not will need to get to grips with Scope 3 accounting, or be forced to take down public goals, or walk back their scope accordingly – neither action is likely to be viewed as favorable to investors that see climate risk as an investment risk.

A transition plan is used to lay out actions and targets that demonstrate an entity’s pathway toward a low-carbon economy, through reducing its absolute and / or intensity-based GHG emissions or concerning exposure. There are many frameworks that set out characteristics of an effective transition plan. This includes broad industry frameworks such as UN Asset Owners Alliance, through to more sector specific guidance used by signatories of the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative issued by the IIGCC, and more besides.

Unlike the frameworks named above, the SEC proposed rule does not provide sufficient guidance on the characteristics of an effective transition plan. For example, this may include disclosure of:

- Base year, target end year and importantly, interim target year(s)

- Climate scenario considered (e.g. 1.5C, 2C, 3C)

- Type of target (e.g. absolute or intensity based)

- Coverage and scope of the target, including narrative on any carve-outs

- Alignment with recognized and suitable frameworks

Without specific disclosure requirements, there is a risk that transition plans may not be comparable nor decision-useful for investors – a concern raised by many commentators.

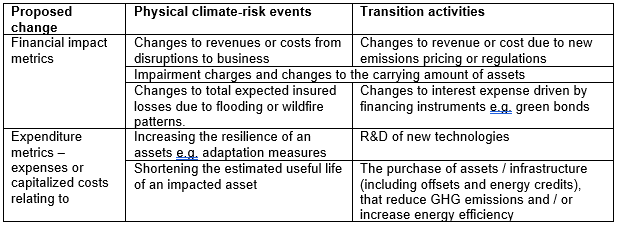

Lastly, but certainly not least, a new Article 14 to Regulation S-X would require a registrant to disclose climate-related financial metrics relating to severe weather events and other natural conditions and / or transition activities.

These financial metrics must be presented on an aggregated line-by-line basis for all negative impacts, and separately, all positive impacts where the impact is greater than 1% of the line item. If collecting Scope 3 data appears challenging, collating these financial metrics will present a gargantuan task for many registrants. Once the data is held, registrants will then face the effort of contextualizing the metrics so they don’t unduly scare investors.

Final thoughts

Overall, the SEC has moved from zero to one hundred in some incredibly far reaching, and challenging, requirements. The proposed rules lack clarity in a number of areas and will surely be revised before final issue. However, I do expect the rules to be materially similar when the final form is issued, with my prediction being year end.

Once introduced, the challenge for registrants is to view the rules “beyond compliance” and embrace the TCFD framework as a pragmatic methodology for climate change preparedness and resiliency. This mindset is essential if the US (and the world) are to achieve a just and orderly transition to a net zero economy.

[1] https://www.sec.gov/comments/s7-10-22/s71022.htm

[2] https://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/2022/33-11042.pdf

[3] The Commission first addressed disclosure of material costs and other effects on business resulting from compliance with environmental law in a 1971 Interpretive Release.

- The 1971 position took two years to codify and reached the final and current form in 1982, after a decade of evaluation.

- In 1975, the Commission also concluded that it would require disclosure relating to social and environmental performance “when the information in question is material to inform investment”.

- In 2010 SEC guidance specifically emphasized that climate change disclosure might, depending on the circumstances, be required in a company’s Description of Business, Risk Factors, Legal Proceedings, and Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations (“MD&A”).

- In 2016, the SEC issued a Concept Release regarding the modernization of regulation S-K including on climate change, noting the growing interest in ESG disclosure among investors and also the often inconsistent and incomplete discourse due to the voluntary nature of corporate sustainability reporting.

- Finally in 2021, input was sought by the SEC on whether current disclosures adequately inform investors. This was made at the same time the federal Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) listed climate change as an emerging threat to the financial stability of the US.

[4] https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2021/07/2021-TCFD-Status_Report.pdf

[6] https://carbonaccountingfinancials.com/

[7] https://www.ukgbc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Scope-3-guide-for-commercial-real-estate.pdf