Thought

Climate Risk Readiness White Paper

1. Why is climate change such an important investment risk for investors in real estate & infrastructure?

A summary of the factors driving change in the real asset markets.

In early 2020, before the pandemic hit, BlackRock’s Larry Fink called out the fact that “Climate Change is Investment Risk”. Three paragraphs of his annual letter stood out, highlighting the connection between material climate risk, their impact pathways, and the drivers of asset value:

“Will cities be able to afford their infrastructure needs as climate risk reshapes the market for municipal bonds? What will happen to the 30-year mortgage – a key building block of finance – if lenders can’t estimate the impact of climate risk over such a long timeline, and if there is no viable market for flood or fire insurance in impacted areas? What happens to inflation, and in turn interest rates, if the cost of food climbs from drought and flooding? How can we model economic growth if emerging markets see their productivity decline due to extreme heat and other climate impacts?

“Investors are increasingly reckoning with these questions and recognizing that climate risk is investment risk. Indeed, climate change is almost invariably the top issue that clients around the world raise with BlackRock. From Europe to Australia, South America to China, Florida to Oregon, investors are asking how they should modify their portfolios. They are seeking to understand both the physical risks associated with climate change as well as the ways that climate policy will impact prices, costs, and demand across the entire economy.

“These questions are driving a profound reassessment of risk and asset values. And because capital markets pull future risk forward, we will see changes in capital allocation more quickly than we see changes to the climate itself. In the near future – and sooner than most anticipate – there will be a significant reallocation of capital.”

On its own, this proclamation from the CEO of the world’s largest asset manager might have created a few ripples in the investment markets, but not create a wholesale market transformation. However, the letter sandwiched an unprecedented period in the history of mankind’s battle with climate change. At the end of 2018, the UN Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) published a Special Report on the impact of global warming of 1.5°C, which provided a stark warning about the consequences of inaction on climate change. In the period between these two events, several other activities took place which reinforce the market change:

- Public opinion about the need to act on climate change shifted significantly in favour of action, in no small part to the meteoric rise in popularity of Greta Thunberg’s ‘Fridays for Future’ school children protests and the disruption caused by other campaign groups, such as Extinction Rebellion (XR) protests, and legal class actions brought forward by student groups around the world.

- Climate science and the quality of climate modelling continues to improve, with recent work showing that the likely outcome of global warming will be between an average global warming of 2.6°C and 3.9°C. This is well above the low-risk threshold of 2°C agreed at the 2015 Paris Climate Summit (COP 21) and the preferred target of 1.5°C.

- Significant capital reallocation towards delivering ESG objectives happened during 2019 and continued into 2020.

These factors, combined with new and forthcoming government regulations, would suggest that climate change and broader sustainability (or Environmental, Social & Governance) issues are here to stay for investors. Their material impact on financial returns is starting to become better understood as more time and money is invested in improving our knowledge and its application in real asset investment markets. Ignorance of these issues is no longer an excuse.

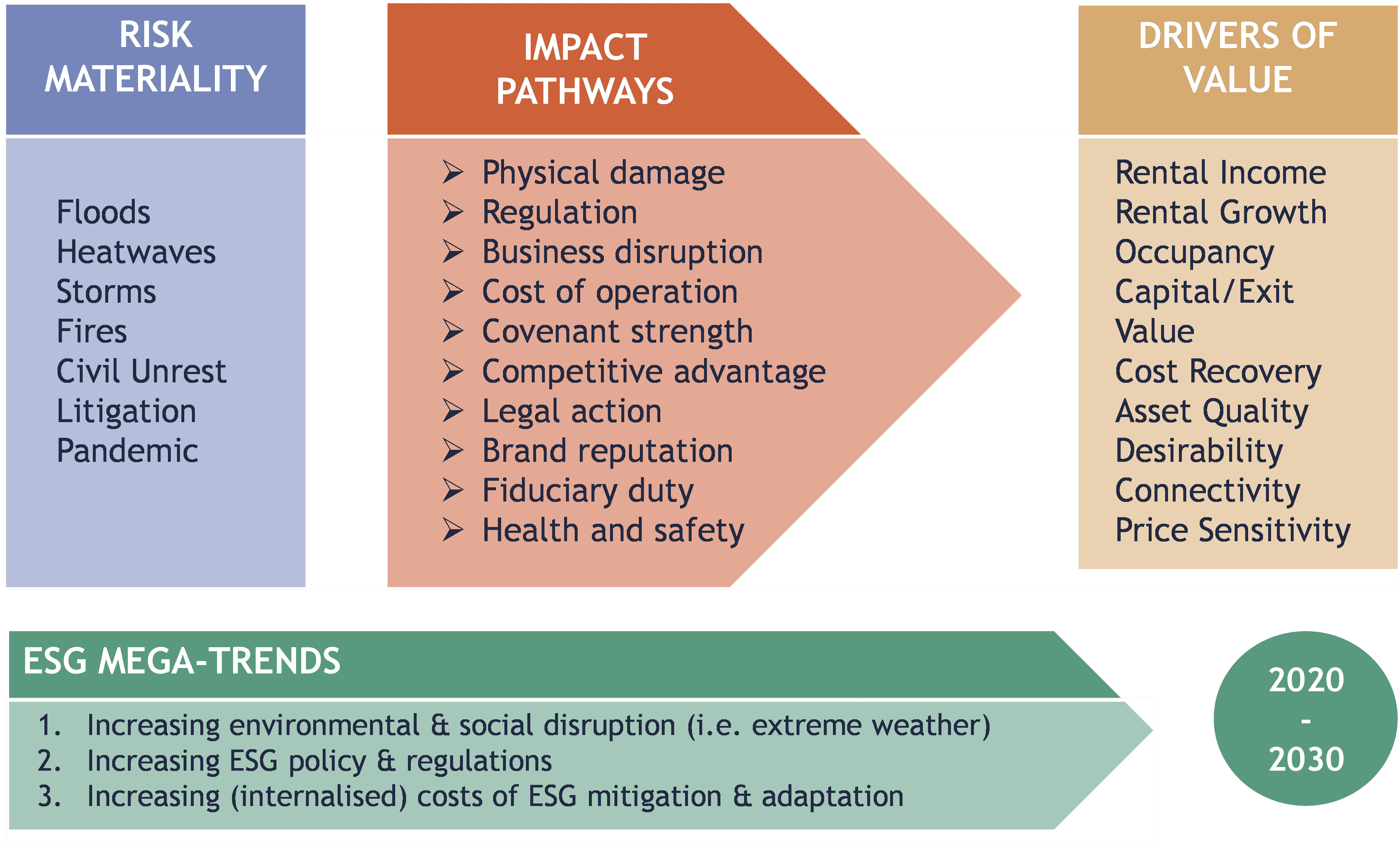

The way in which climate risks are being understood is in 3 categories:

- Physical risk

- Transition risk

- Litigation, or Liability, risk

For physical risk, the first step is to understand which climate-related hazards present a material risk, both now and over the period of an investment, including the disposal value. For instance, the materiality of a flood hazard could increase over time as climate change creates the conditions for more frequent and/or more severe floods causing damage or disruption to an asset. The impact pathway for that hazard could be that the repair costs and frequency of the floods means that an asset becomes uninsurable. Another impact pathway could be that the flooding makes it impossible to access an asset, which in turn reduces occupancy and the related revenue that generates.

The complex nature of the changes brought about by our warming climate means that the risk hazards and impact pathways could influence the drivers of asset value in multiple ways.

Whilst some of these material risks are apparent today, there are many others which will become much more visible over the coming decade. The trends that we see which could accelerate changes to asset value include: increased environmental & social disruption; increasing government regulation; and the internalisation of these costs to mitigate climate change and to adapt to the consequences. Companies and asset managers need to be prepared to avoid the risk of litigation.

2. What are the expectations for how investors and asset managers will respond to climate risks?

There is increasing certainty about how to be prepared to action.

Climate-related financial risk is a new topic for investors. In 2015, Mark Carney, as the Governor of the Bank of England, gave a speech which warned of the threat of climate change to financial stability. He spoke of the “Tragedy of the Horizon” where inaction on climate change today imposes a cost on future generations that the current generation has no direct incentive to fix. Meaning that the time horizon for decision-making in typical business and investment cycle is not suitable for tackling the catastrophic impacts of climate change.

Earlier in the same year, the G20 asked the international Financial Stability Board (FSB) to report on how climate change risks could be accounted for in the financial sector. Both of these events were precursors to the UN Climate Summit (COP21) in Paris later that year. The international political agreement reached at COP21 was a watershed for international climate policy as governments agreed that a target of limiting global warming to 2°C is a necessity to avoid catastrophic changes and that getting well-below this figure was desirable, so 1.5°C is the stretch target. To achieve this target collectively, we need to stabilise greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, measured in tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent, by 2050 – also known as getting to Net Zero Carbon or being Carbon Neutral by 2050. Failure to do this will mean that the Earth will continue to warm and the financial losses will be much greater.

This growing recognition that climate change and the related financial risks have to be considered in the financial markets led to the announcement during COP21 to establish a Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) under the auspices of the FSB and chaired by Michael Bloomberg. The TCFD will develop voluntary, consistent climate-related financial risk disclosures for use by companies and asset managers in providing information to investors, lenders, insurers, and other stakeholders. Considering the physical, liability and transition risks associated with climate change.

One year later the TCFD published its Recommendations for consultation, which were finalised by the summer of 2017. Over the last 3 years since the Recommendations were released there has been considerable efforts made by the FSB-TCFD to build support for their adoption by actors in the financial markets. Recognising that preparing an organisation to embed a comprehensive response to climate-related risks could take 3 years.

In parallel to this promotion of TCFD over the last 3 years, GRESB has been piloting a Climate Risk Module as part of their annual disclosure and benchmarking process specifically for real estate and infrastructure. Other international Environmental, Social & Governance (ESG)/Sustainability reporting standards have also promoted more effective consideration of climate risks and preparedness.

Every year the UN published an Emissions Gap Report. In 2019, the report stated that we need to reduce global GHG emissions by 7.6% every year between 2020-2030. If we don’t start that level of reduction now, then by 2025 we will have to reduce emissions by 15.5% every year to hit the target and this will be more costly and still necessary. The later that we leave act to mitigate GHG emissions, the higher the annual cost of mitigation action and the increased likelihood of increase cost of adaptation to a changed climate. Many companies have now adopted science-based targets aligned with the UN to reduce emissions and to get to zero. Governments are following suit.

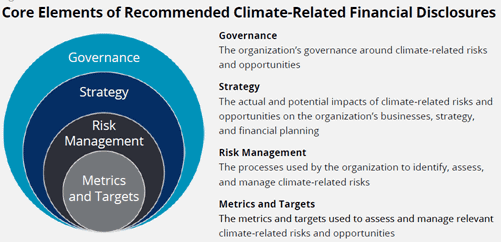

The Recommendations of the TCFD are not requirements, they provide voluntary guidance intended to help companies acting in the financial markets to better manage and disclose climate-related financial information. There are four key design features of these recommendations:

- They can be adopted by all organisations

- They are intended to be included in financial filings

- They are designed to solicit decision-useful, forward-looking information on financial impacts

- They have a strong focus on risks and opportunities related to the transition to a lower-carbon economy

As investors and asset managers consider how climate risks can be considered in their organisations, the TCFD core elements shown below provide a useful structure for getting the organisation ready to disclose the relevant financial information. The TCFD recommendations should be familiar in structure to CFOs and are reinforced by a recent opinion from IASB which recommends that IFRS reporting should include climate risk disclosure. This is almost a precursor to action on individual assets as the structure allows for a strategic approach to be systematically embedded in risk management and then embedded across all levels of the organisation, from corporate through entities / funds, investment, disposal, development and asset management processes.

EY’s ‘Global Climate Risk Disclosure Barometer’, which reviews the disclosure of 500 companies from 18 countries, shows mixed progress in 2019 in the adoption of the TCFD recommendations. Most progress has been made on ‘Metrics & Targets’ and ‘Governance’, whilst the quality of ‘Strategy’ and ‘Risk Management’ are the least developed. Their sector by sector comparison shows that the ‘Real Estate’ and ‘Asset Owners & Asset Managers’ sectors have made the least progress, in terms of coverage and quality. Suggesting that there is significant progress to be made by real estate investors and asset managers to be ready to manage and report on climate-related financial risks.

Whilst the TCFD Recommendations are voluntary, they are a precursor to mandatory disclosure in Europe resulting from the EU ‘Action Plan on Sustainable Finance’. At least for publicly listed companies and funds. Regulations which begin in 2021 will start this process of increasing disclosure.

The EU Taxonomy Regulation has set out a standard set of environmental impact categories, including Climate Mitigation and Climate Adaptation. This Regulation has established the principle of Do No Significant Harm (DNSH) and has set thresholds for what a ‘Significant’ positive impact looks like. It is expected that companies active in the EU will provide disclosure aligned to this taxonomy and it will provide investors with a common lexicon to use in global due diligence and in the scrutiny of fund performance as we experience more capital flowing into ESG funds.

3. How can a company ensure that they are prepared as an organisation to discharge their fiduciary duty?

There are clear steps that can be taken to be prepared to manage climate risks.

EVORA Global advises real estate and infrastructure investors and asset management in Europe and the USA who have global funds, with assets under management in over 30 countries. Our experience with these organisations has shown that there is a broad spectrum of Climate Risk Readiness. From the largest to the smallest they are considering how they respond to climate-related financial risks. They are having to do so now to ensure that they have access to the best capital.

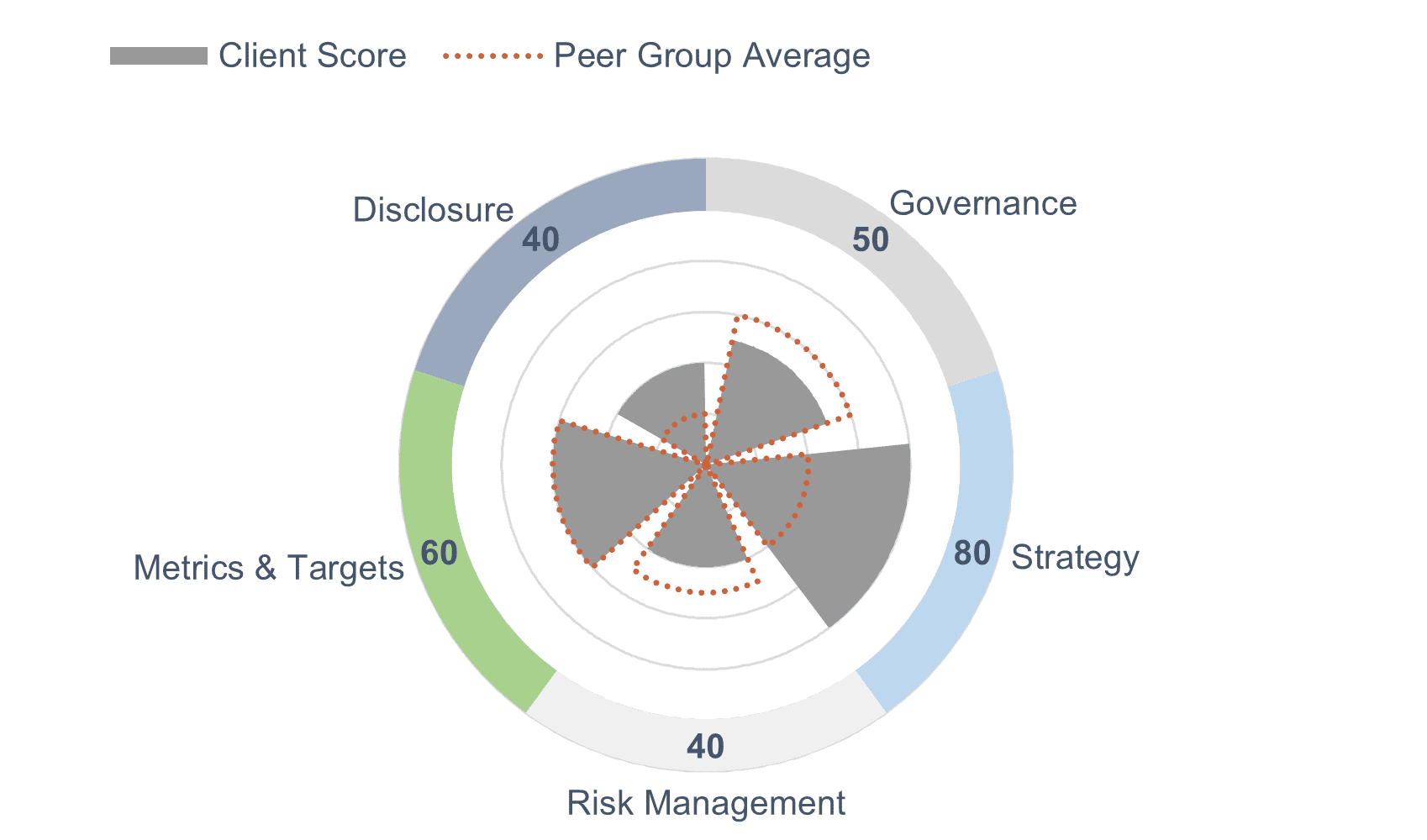

To get ready, an organisation can undertake a Climate Risk Readiness Gap Analysis, which can be displayed on our EVORA Climate Risk Readiness Radar and compared to their peers. This assessment looks at the organisational readiness and is aligned with the TCFD Recommendations and upcoming regulations. It can be supplemented with fund and asset-level scoring of climate risk exposure and management readiness.

The EVORA Climate Risk Readiness Radar provides an evidence-based scoring mechanism to compare progress. Under each of the five categories – Governance; Strategy; Risk Management; Metrics & Targets; and Disclosure – there are five levels of organisational readiness, and each level has an associated set of actions. For instance, Level 1 Governance required all Board member are trained to understand their fiduciary duty regarding climate risk, including their main materials risks and disclosure responsibilities and requirements. The associated set of actions includes a risk materiality assessment of the organisation’s assets; formal training for the Board; and a declaration by the Board that all of its members have confirmed their understanding.

By understanding this gap analysis of organisational readiness, it is then possible to set out a roadmap for the coming years. This will enable the organisation to communication a clear plan to investors and other stakeholders.

Level 1 Strategy contributes to Level 1 Governance as it requires an assessment of material physical and transition risks through the use of climate scenario analysis. This should be segmented by time horizon, geography and/or sector. As this modelling is a standard requirement for getting to grips with climate risk there are several data analysis software tools now available on the market. The EVORA team has been evaluating which specialist data analysis partner to work with.

The majority of data services available today are focused on analysing physical risks, like the extreme weather impacts of heat, flooding and storms. Our approach to assessing the materiality of physical risks, and to answer the question “so what?”, is in three broad phases:

- A portfolio or fund screening of a range of weather hazards to prioritise a deeper investigation of the high-risk assets,

- An assessment of the impact pathways to create a shared understanding of how the hazard risk could impact the drivers of asset value, and

- A detailed investigation and assessment at asset-level of the specific, material hazards which impact value and are prioritised from 1 & 2 above.

These three phases provide a deeper understanding of risk than a high-level screening can provide. The intention is that this provides a detailed evidence base on which to define a credible, effective and appropriate climate risk strategy and the related processes for risk management. Both of these areas of climate risk management are presently considered weak in most company disclosures.

Today, there is not an existing data partner which can deliver on all three of these phases end-to-end so we collaborate with specialist partners to deliver a comprehensive Climate Risk Materiality Portfolio Assessment service for fund managers. EVORA usually extends this assessment to also cover Transition Risks, in particular forthcoming regulations which could affect value.

These two EVORA Assessments on Readiness and Materiality are essential building blocks in understanding the effort and exposure for an organisation’s preparedness on climate-related financial disclosure. The outputs will provide a clear roadmap for integration over the next few years.

Investor expectations of climate risk have moved on quickly over the last few years. Our expectation is that this acceleration in understanding and scrutiny will continue. Reinforced by new regulations, particularly the regulations flowing from the EU Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth and Paris’ climate mitigation goals, ever-improving climate models and continued emissions of greenhouse gases which are not in line with a Net Zero Carbon trajectory. Those investors who are not prepared are much more likely to acquire assets which are at risk, that is not aligned with science-based decarbonisation pathways and/or exposed to a changed climate. The need for organisational preparedness, embedded across all aspects of investment – i.e. asset management; acquisitions; developments; and disposal – is essential portfolio management. Good quality data and information is vital in delivering expected returns in a market which is transitioning to become low-carbon and adapted for a changed climate.

EVORA is engaging with companies and relevant institutions to better prepare the real estate and infrastructure sectors for climate mitigation and adaptation disclosure. The approach outlined in this paper is difficult to fast-track in large organisations to ensure it is properly integrated. One of the biggest challenges which remains is solving the ‘Tragedy of the Horizon’ as this means that the actions required in an investment portfolio cannot always be taken within the investment lifecycle. The TCFD initiative is designed to address this challenge and, to be successful, this requires early and comprehensive adoption by real estate actors. We would recommend to our clients that early action on climate risk reduces the risk of Litigation or Liability Risk, as well as falling disposal values of asset exposed to Transition and Physical Risks. The steps outlined here will guide substantial and measurable progress.