Thought

Embodied Carbon and its Role in Achieving Net Zero Carbon

- Embodied Carbon accounts for the total greenhouse gas emissions released to the air as a result of constructing a building

- Commitments have been made to achieve Net Zero Carbon by 2050, Embodied Carbon must be considered and reduced to achieve this

- Climate change poses a number of financial risks

- Embodied Carbon studies can increase climate resilience and therefore reduce risk and increase return

What is Embodied Carbon?

Have you ever walked past a building site and wondered where all the materials have come from? Whether the timber began life as a tree in the UK or abroad? While I was on work experience on one of my Father’s building sites, I found the idea that materials from potentially all around the world have come together to make something new, fascinating. I wondered about the work and energy that went into getting them onto the building site; first the raw materials are extracted, then transported to an industrial site where they are processed into a product, then transported again to the construction site and finally put into place. At each of these stages, energy is consumed and therefore emissions of greenhouse gases are released to the air (measured as emissions of CO2 equivalent, in this article, ‘carbon’). As such, each individual building material has a certain amount of carbon associated with it – the emissions released as a result of that product’s life. These emissions are the embodied carbon of the product, and as a wise person once said, ‘One brick does not a house make’, so the total emissions from all of the products and processes that go into making a building, form the total embodied carbon of that building.

The embodied carbon during construction, along with the operational carbon during the building’s life, such as energy used for HVAC, in addition to the end of life activities such as demolition or deconstruction – depending on where the system boundary is considered – all sum to the total carbon that is released as a result of the building’s life. Accounting for and reducing total carbon emissions has never been more important as the effects of anthropologic climate change continue to devastate parts of the world.

Why is Embodied Carbon becoming more important?

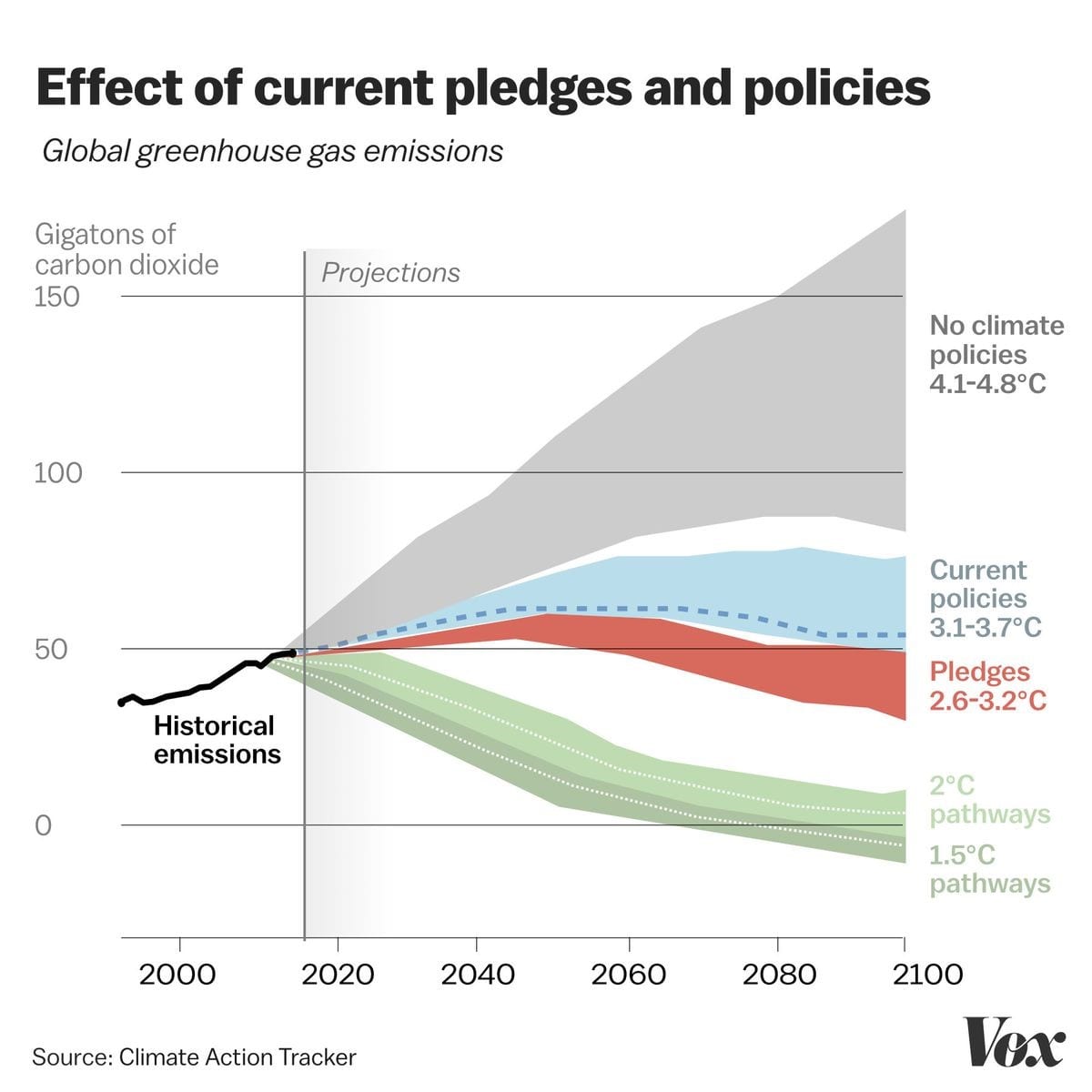

Following the Paris Agreement in 2015, governments around the world agreed that climate change must be limited to ‘well below 2⁰C’, and in our industry a figure of 1.5⁰C has been widely adopted as the target maximum [1]. This can only be achieved by countries and industries achieving a balance between carbon emissions and carbon sinks, resulting in the amount of carbon released to the atmosphere totalling ‘Net Zero’, by 2050 [2]. These commitments are binding, and increasingly severe fines will be issued to those who emit excessive carbon. To be successful, is it vital that governments and companies alike create pathways to Net Zero, to plan the transition to a decarbonised future and ensure that this future aligns with a 1.5⁰C trajectory (see figure 1). It is also important to consider both the total volume of emissions and the rate at which they are released, therefore change must happen in the short term, as sudden reductions in 2040 for example, will not be as successful in limiting the impact of climate change [3].

In commercial real estate, 23 of the leading commercial property owners have committed to becoming Net Zero by just 2030, under the Better Building Partnership Climate Change Commitment [4]. Under this agreement, scope 3, or all other greenhouse gas emissions that occur due to its activities, but which it has no direct ownership or control over, are also included, which covers embodied carbon. With current technology, generating embodied carbon through construction is unavoidable, therefore the only options to balance embodied carbon are to reduce it as much as possible, then offset the rest.

What are some of the risks posed by climate change?

The EU Emissions Trading Scheme operates under a ‘cap and trade’ principle, meaning although offsets can be brought, they will be capped and reduced over time and eventually there is a risk that offsets will no longer be available, or the prices be too high to be economically viable [5]. Similarly, in the voluntary offsetting market, there are a finite number of projects delivering offset ‘credits’, and over time, the low hanging fruit will be depleted so that financing projects becomes ever more expensive. This could lead to the more significant risk of fines being imposed for excessive emissions, along with a carbon tax on the remaining embodied carbon. Furthermore, although industry leaders have placed more responsibility on themselves to improve climate resilience and reduce emissions, there is a transitional risk that regulation will change in the future, leaving some assets stranded. For example, regulation could restrict the use of inefficient technologies or improve carbon accounting and bring more sources of emissions into scope. Should companies refuse to act now and continue with business as usual, they risk being caught out later and be forced to make sudden adjustments to align with new regulations, which could prove extremely costly. Such regulations include the draft new London Plan policy GG6: Increasing efficiency and resilience [6], this policy requires those involved in planning and development to improve energy efficiency and support the move to a low carbon circular economy. As such, planning permission could be refused to developers who do not align to this policy.

The requirements around disclosing climate resilience and environmental performance is becoming more commonplace, the Taskforce for Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) is increasing transparency in this area by requesting organisations disclosure their climate-related financial risk publicly [7]. While currently voluntary, emerging Sustainable Financial Disclosure Regulations mean that this is unlikely to stay this way long term. There is therefore a reputational risk that stigmatisation of poor climate resilience could grow, and negative stakeholder feedback could arise. This in turn could prove material should a company lose out on investors because of this, who will be aware of the various financial risks climate change poses and view these as investment risks.

The physical risks of climate change will also be material for any entity with physical assets, which includes real estate, property could be damaged, for example by increased rainfall or flooding, or induce additional operating costs, for example higher temperatures leading to increased use of HVAC equipment, thus requiring additional maintenance. Therefore, it is in the best interest of the industry to limit the physical effects of climate change by sticking to a 1.5⁰C trajectory, where is it widely reported that these risks will be more significant at 2⁰C and above [3].

It must be noted that there is risk in adopting new technology, as it is unknown how that technology will perform in the long term and could have unforeseen consequences, for example new HVAC equipment could cause a building to overheat in certain conditions, potentially contributing to the urban heat island effect. However, new technology and innovations will be required if climate change commitments are to be met, which is why it is important that there is collaboration across the industry to develop and trial new technology and share best practise, which is already evident in companies with robust Net Zero Carbon Pathways, such as Derwent [8]. Considering the challenge of reducing scope 3 emissions, such as during tenant fit out, since developers do not control this activity directly but are still responsible for the carbon, collaboration and stakeholder engagement will be of great importance.

Where does embodied carbon fit into the bigger picture, and how can it increase climate resilience?

Embodied carbon studies can help to increase climate resilience in a number of ways, for example, as such studies become more widespread, increased accountability for developers will help reduce redundant building and encourage developers to think critically about their projects, potentially leading to increased major refurbishment works in preference to new construction. Furthermore, embodied carbon studies can encourage leaner and lighter building, as the simplest way to reduce embodied carbon is to use fewer materials, through identifying and removing redundant building elements. Material hotspots with high carbon intensity can also be identified, and alternatives with lower embodied carbon, such as recycled and reused materials, are promoted which also helps to progress towards a circular economy as highlighted in the European Green Deal [9]. Moreover, by considering embodied carbon during the design phase, strategies can be put in place to reduce it, such as designing for deconstruction, allowing building elements to be disassembled and reused or recycled more easily at the end of life.

Best practice dictates that accounting for embodied carbon emissions falls both with the initial developer and first-time purchaser of buildings [10], because both can have an influence over the design and construction which takes place. Whilst later purchasers of that building will not assume liability for the embodied carbon, it does present an increasing transition risk to developers and purchasers of new buildings, because over time, embodied carbon will contribute an increased proportion of the overall building lifecycle carbon as operational emissions fall. As a financial value is assigned to this risk, the incentive to minimise embodied carbon in future will become ever more critical in investment decision making.

Fortunately, years of varying approaches to measuring and managing embodied carbon have now given way to increased industry consensus, through the publication of key guidance, such as the RICS Whole Life Carbon Assessment for the Built Environment [11]. Several tools now also exist to enable efficient construction of embodied carbon models and identification of best practice enhancements. EVORA utilise One Click LCA for this purpose, saving clients precious time and resource in fast moving design processes.

Embodied Carbon Studies should also be incorporated into a Net Zero Carbon Pathway, as this sends a clear market signal that the financial risks of climate change have been understood and accounted for, which in turn is likely to attract investors, improve stakeholder relations, and could even attract tenants and increase asset value as the market develops over time. However, it is important to plan out a pathway sooner rather than later, reducing the likelihood that a sudden transition is required, which in turn reduces the financial risk of climate change.

If you are interested in getting help on your Net Zero journey, you cancontact our Climate Resilience team.

References

[1] Paris Agreement, United nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015

https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf

[2] World Green Building Council, 2020

https://www.worldgbc.org/advancing-net-zero/what-net-zero

[3] IPCC, Global Warming of 1.5⁰C, 2018

[4] Better Building Partnership, Climate Change Commitment, 2019

[5] European Commission, EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), 2020

https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets_en

[6] Mayor of London, New London Plan, 2020

https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/planning/london-plan/new-london-plan

[7] TCFD, Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, 2017

https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/app/uploads/2017/06/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report-11052018.pdf

[8] Derwent, Net Zero Carbon Pathway, 2020

[9] European Commission, A European Green Deal, 2020

https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

[10] UKGBC, Guide to Scope 3 Reporting in Commercial Real Estate, 2019

https://www.ukgbc.org/app/uploads/2019/07/Scope-3-guide-for-commercial-real-estate.pdf

[11] RICS, Whole life carbon assessment for the built environment, 2017

Image

[12] Climate Action Tracker, 2020